Article Highlights

-

A doctor, a health researcher, and a public health official in Washtenaw County, Michigan, share their pandemic stories and how NIH has helped.

-

Learn how one community — like many across the country — has battled COVID-19 since early 2020.

-

Testing, treatments, and vaccines have improved COVID-19 outcomes.

Elizabeth M. Viglianti, M.D., M.P.H., M.Sc., got her first look at how COVID-19 could affect her life at a conference for intensive care doctors in February 2020 in Florida. She sat in a conference center and listened as doctors in Wuhan, China, talked over video about their experience with this new respiratory disease. She flew home to Ann Arbor, Michigan, where she is an intensive care unit (ICU) doctor and researcher at the University of Michigan and the Ann Arbor VA Medical Center, and waited for the first COVID-19 cases to appear. “It was terrifying,” she said.

When COVID-19 emerged, doctors, researchers, and public health officials were scrambling to get a grip on a new disease. Nearly two years later, Viglianti has had many patients die from COVID-19, but she has also saved many lives as she and her colleagues tried new treatments and incorporated research findings into their practice.

Since the early days of the pandemic, research has helped in many ways. New treatments have improved people’s chances of survival. NIH’s Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx) initiative has helped develop and disseminate tests, and decades of NIH-funded research on mRNA vaccines provided the foundation for safe, effective vaccines against the novel coronavirus.

For an example of how these contributions have improved life during the pandemic, we turned to Washtenaw County, Michigan, which is home to more than 350,000 people in cities, suburbs, and rural areas. As doctors, researchers, local health officials, and other community members there contemplate what it means to be heading into year three of the pandemic, they can also see how things have changed since spring 2020.

Dr. Elizabeth M. Viglianti (above) and her colleagues at the Ann Arbor VA Medical Center have seen firsthand how research on treatments and vaccines has improved outcomes for patients with COVID-19.

Dr. Elizabeth M. Viglianti (above) and her colleagues at the Ann Arbor VA Medical Center have seen firsthand how research on treatments and vaccines has improved outcomes for patients with COVID-19.

Fighting for Lives in the ICU

Washtenaw County saw its first positive test result on March 11, 2020. Within a month, Viglianti and her ICU colleagues were seeing a wave of very sick people. Both the University of Michigan and the VA medical centers opened special COVID-19 ICUs.

“There was this gust of energy, of everyone unifying and ready to battle,” Viglianti said. At weekly meetings, ICU doctors discussed what they were seeing and the latest evidence on taking care of people who were critically ill with COVID-19. “Early on, there weren’t any therapies,” Viglianti said. “The only thing we had was supportive care.” Based on a study done several years earlier in France, the ICU staff started turning patients onto their stomachs part of the time; the staff found that it helped, and they continue to do so today.

Late in the summer of 2020, a study from Brazil gave new hope: Dexamethasone, an inexpensive medicine that suppresses the immune system, helped COVID-19 patients in the ICU. “That was the biggest surprise, the biggest relief,” Viglianti said. That simple medicine has kept a lot of people off ventilators.

As time went on, other therapies began to appear. Although early hopes for the malaria drug hydroxychloroquine faded, thanks to an NIH-funded trial that found the medicine had no benefit in COVID-19 cases, better treatments came along. Monoclonal antibodies were found to help, including for people who were not sick enough to be hospitalized. After an NIH-sponsored study, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the antiviral drug remdesivir for use in treating COVID-19.

While the ICU staff worked to keep people alive through the fall of 2020, the success of vaccine trials brought them hope. “When we hit December of 2020, when the vaccines came around, there was this huge sense of relief,” Viglianti said. She knew her own immune system would finally be ready to fight the virus and that the pandemic would surely slow as everyone in the community got vaccinated.

Many people with COVID-19 have ended up with long stays in the ICU; Viglianti has her own NIH-funded research project on how to identify such patients. In 2021, she began collecting data from her colleagues to understand how they make predictions about how a person will fare in the ICU and whether they are likely to stay for a long time.

“I think that’s what keeps us going, as this pandemic seems to want to never end: We’re still providing the best care. At the end of the day, it’s still about people.” — Elizabeth M. Viglianti, M.D., M.P.H., M.Sc.

At the beginning of summer 2021, it seemed like things might get back to normal. But in July, the Delta variant fueled a new surge that never quite ended. As of March 2022, about a third of people in Washtenaw County are not yet fully vaccinated. (Fully vaccinated means receiving all primary doses of an mRNA vaccine or a primary dose of J&J/Janssen vaccine.) “During the first wave, while it was super dark and there were lots of deaths, there was also a lot of energy and support,” Viglianti said. “I think subsequent waves have just been harder. The hits have been harder even though the deaths have been fewer.”

Nearly all the ICU patients she sees with COVID-19 now are unvaccinated. “The hardest are those who are unvaccinated and are still adamantly denying that COVID exists,” she said. She has meetings with family members who believe the disease is made up by doctors or who desperately want treatments that have been proven ineffective or even harmful.

These difficult, emotional conversations wear on the ICU staff, Viglianti said. But the intense years of the pandemic have given Viglianti constant reminders of why she went into medicine. “I think that’s what keeps us going, as this pandemic seems to want to never end: We’re still providing the best care. At the end of the day, it’s still about people,” she said.

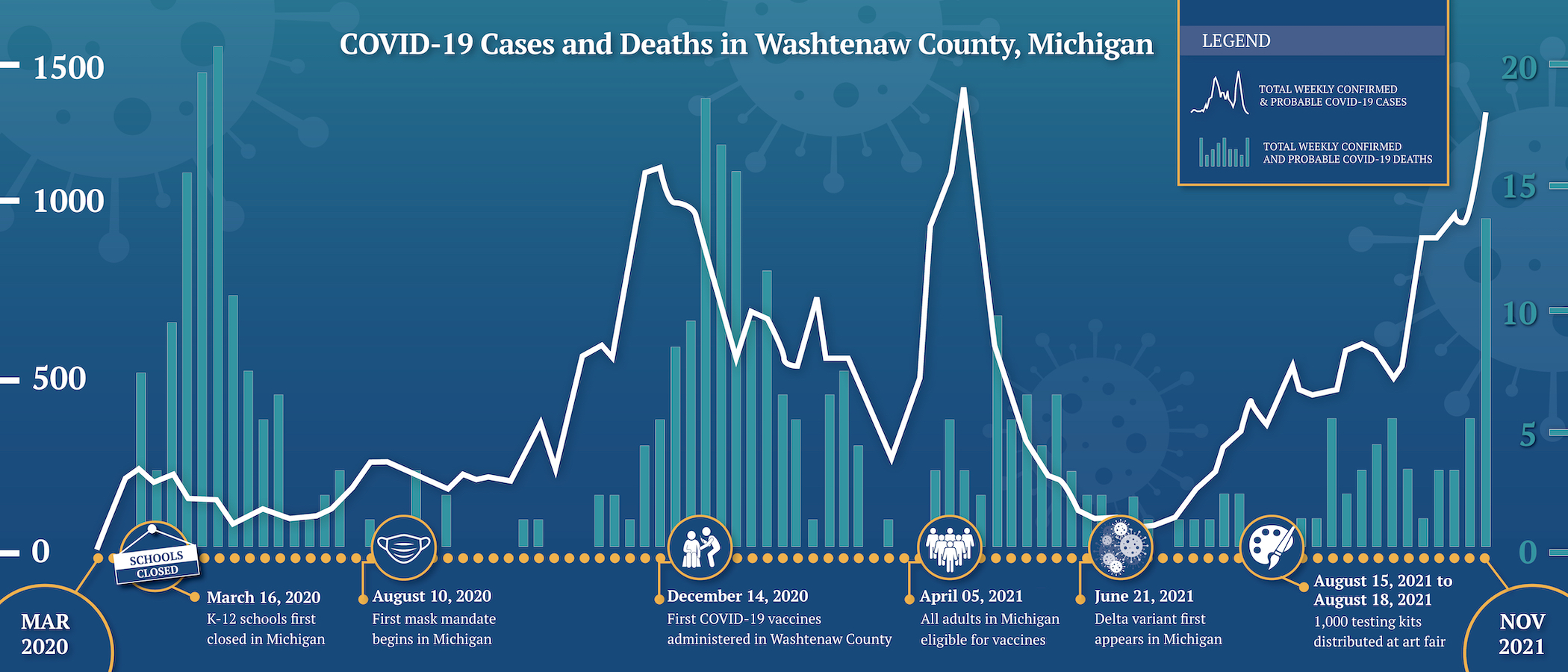

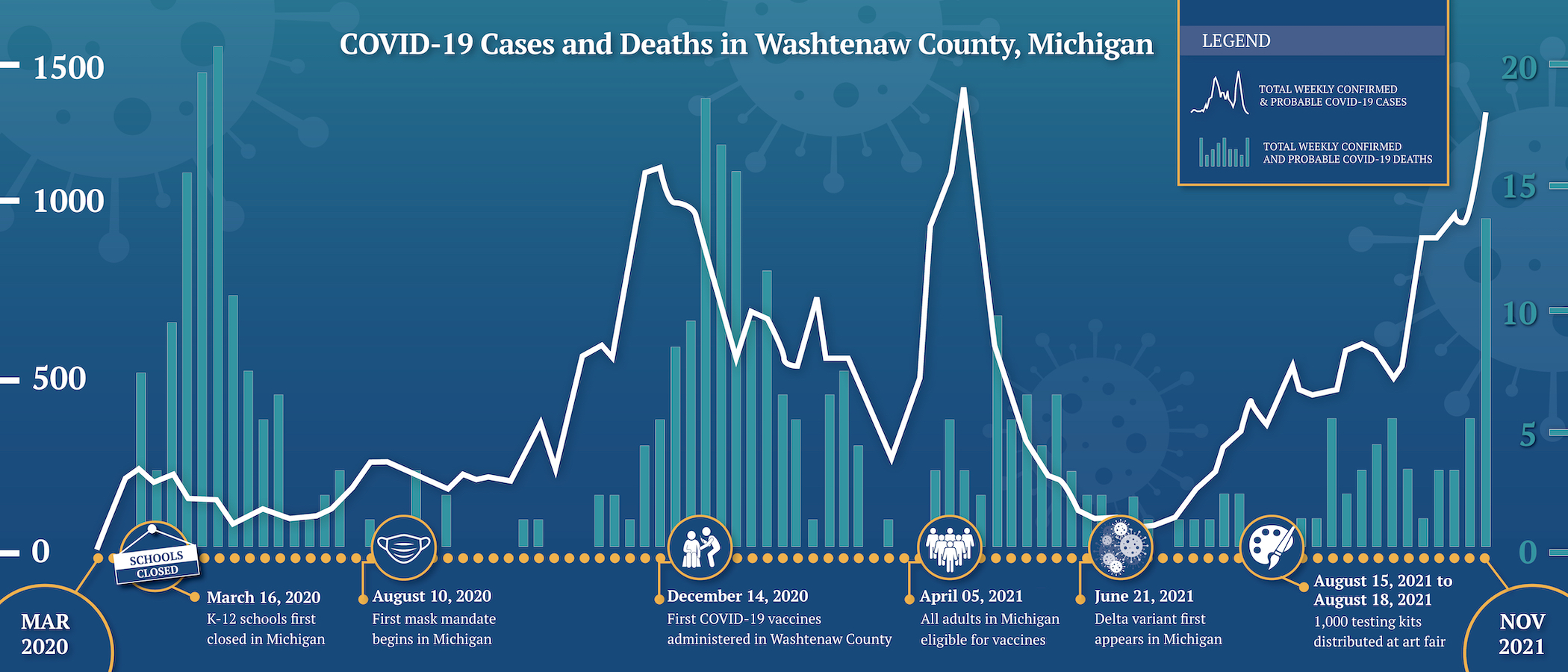

Over the course of the pandemic, a rise in cases (white line) has been followed by an increase in deaths (green bars). Each peak in cases in Washtenaw County is higher than the one before. The number of deaths, however, has not increased nearly as much. That means more people who get COVID-19 are surviving, thanks to advances in vaccines, treatments, and testing. (Note: Tests were scarce in spring of 2020, so cases were likely higher than the numbers shown.)

Over the course of the pandemic, a rise in cases (white line) has been followed by an increase in deaths (green bars). Each peak in cases in Washtenaw County is higher than the one before. The number of deaths, however, has not increased nearly as much. That means more people who get COVID-19 are surviving, thanks to advances in vaccines, treatments, and testing. (Note: Tests were scarce in spring of 2020, so cases were likely higher than the numbers shown.)

Testing for Public Health

Juan Marquez, M.D., M.P.H., started a new job as the medical director for Washtenaw County in July 2019 — he only had about six months to settle in before the pandemic hit. He has hardly had a break since.

In February and March 2020, Marquez and his colleagues were the gatekeepers for scarce tests, taking calls from health care providers and hospital infection control teams. “We would get calls at 2:00 in the morning,” he said. Their first sample from a possible COVID-19 patient, in January 2020, went off to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and tested negative. But on March 11, the first two positive results came, and the virus was spreading widely soon after.

Since early in the pandemic, testing has been seen as an important part of the return to normal life. Because people without symptoms can spread the virus, testing is the only way to find many infections — and to know who needs to isolate to avoid passing it on. But it takes time for scientists to develop tests for a new virus and for test production to ramp up.

A big change in testing came about in the summer of 2021. Washtenaw County was one of the sites for Say Yes! COVID Test, a joint NIH and CDC program to study how frequent at-home testing can reduce the spread of COVID-19. Through that program, the county health department distributed at-home rapid antigen tests to households. The tests were developed with NIH funding and supplied through the NIH RADx initiative.

When distribution started in June 2021, case numbers were low, and so was interest in testing. “For the first month, we would go to events and we could give out maybe one or two test kits. People didn’t want them,” Marquez said. As the Delta variant surged later in the summer, however, so did interest in testing. Across Michigan, health departments working with Say Yes! COVID Test — including Washtenaw County — distributed 453,200 at-home tests in boxes of two, providing 200,000 in person and 253,200 through a website.

Communities Say “Yes!” to COVID Tests

NIH, CDC, and state health departments are working together to distribute free at-home tests to keep communities healthy.

Home testing was a new way of thinking for health officials like Marquez. They’re used to receiving test results so they can keep track of disease and check in with people in isolation or quarantine, as they did early in 2020. “The thought of using home antigen tests was just a little bit unnerving,” Marquez said. “Those aren’t reported to us. It’s not following the process we have.”

But he could also see the advantages. For one thing, a drive-through testing site requires about 20 staff members and may be able to test a few hundred people in a day. However, in one day at the Ann Arbor Art Fair in July 2021, Marquez and a handful of colleagues distributed more than 1,000 tests, giving community members a tool they could use to help avoid spreading the virus. The health department shared clear information on what to do if a test was positive, and Marquez could see how relieved community members were to have the tests.

“Once we participated in it, and we saw how successful it could be, it shifted what we think our tools are,” Marquez said. For example, the health department has worked with schools in a neighboring county to use home testing to shorten quarantine times.

With support from NIH, researchers at the University of Michigan Health spread the word about COVID-19 prevention and protection measures including wearing masks and getting vaccinated — such as this image promoting the Community Vaccine Gallery. Image courtesy of Michigan CEAL.

With support from NIH, researchers at the University of Michigan Health spread the word about COVID-19 prevention and protection measures including wearing masks and getting vaccinated — such as this image promoting the Community Vaccine Gallery. Image courtesy of Michigan CEAL.

Getting Vaccines to Everyone

From the beginning of the pandemic, Erica Marsh, M.D., M.S., FACOG, noticed who was being most affected. Marsh is a reproductive endocrinologist and infertility specialist at the University of Michigan Health in Ann Arbor. She also works on an NIH-funded grant to study racial disparities in reproductive health.

In Washtenaw County, African Americans make up only 12% of the population — but by the summer of 2020, more than 25% of people who had died of COVID-19 in the county were African American. The hardest-hit areas were in Ypsilanti, a city near Ann Arbor with a high proportion of African Americans and a high poverty rate. At the same time, in the wake of George Floyd’s death, people across the country were paying more attention to police violence and health disparities. “All of that was just weighing on me, as a human being,” Marsh said.

In August 2020, Marsh was about to go on vacation when she got an email about funding for the NIH Community Engagement Alliance (CEAL) Against COVID-19 Disparities. CEAL works closely with the communities most affected by COVID-19, and with CEAL support, Marsh knew she could make a difference for people in her area. She knew the opportunity was more important than her vacation, so she and her colleague Barbara Israel at the University of Michigan School of Public Health spent most of that week working on the application. “We turned in that grant, found out we were funded, and hit the ground running — and it’s been nonstop since,” she said.

In the fall of 2020, Marsh’s CEAL team focused on how to get the word out about masks, social distancing, and handwashing. People from hard-hit communities told the team that they wanted to hear from their own neighbors, not just national voices. So the team started a communications contest, Take the Mic, to share community members’ messages about preventing transmission.

When vaccines became available, CEAL quickly shifted gears. Marsh’s team has focused on getting people the facts they needed to make an informed decision about the vaccine and trying to understand the reasons for hesitancy. She was frustrated that people kept saying minorities were refusing to get vaccinated. “There were many people who were hesitant, but many people who wanted the vaccine just didn’t have access. They couldn’t take time in the middle of the day to go to a stadium and stand in line,” she said.

Marsh and her colleagues partnered with faith-based and public health organizations to get vaccines to residents of Ypsilanti and other places throughout the four counties covered in their CEAL grant. The group has supported vaccination clinics in churches, community centers, and schools. The vaccine itself comes from the state and the counties, but Marsh’s team provided everything else, from tables and easels to masks and hand sanitizer. The team supported hundreds of vaccine events in the summer and fall of 2021.

The CEAL team also created a community gallery where people could upload a picture of themselves and a message about why they got vaccinated. The messages helped counter the deluge of vaccine misinformation, Marsh said. “What we realized is, if you get everyday people to be a voice of truth, that’s relevant to their neighbor, to their family member, to their church member, to their mosque member — that was very powerful.” She said it was impressive to watch communities and neighborhoods in Washtenaw County mobilize and take action to help keep one another safe.

Marsh, her team, and community leaders are continuing to work together to fight COVID-19, and she is proud of the work they’ve done. “I did it because it was the right thing to do, and I knew that I wanted to contribute to the end of COVID,” Marsh said. “I’m not an infectious diseases doctor, but I am a citizen who cares about my community.”

Looking Forward

In December 2021, Michigan was nearly overwhelmed with COVID-19 cases, including Washtenaw County, where Marquez said the hospitals were near capacity. “We hoped we’d be in a different position,” he said.

Looking back, however, it is easy to see how much better things are now than early in 2020, Marquez said. When the Omicron surge began in December 2021, weekly cases in the county shot up, eventually reaching more than four times the previous high point of April 2021. But the number of weekly deaths remained close to the levels at the very beginning of the pandemic. “We’re head and shoulders above where we were,” he said. “We know much more about how the virus spreads. We have treatments that are keeping people alive. Vaccination is effective.” And NIH-funded researchers continue to work on new ways to help health care providers and communities fight COVID-19.

An official website of the United States government

An official website of the United States government