Article Highlights

-

Studying the safety and effectiveness of vaccines in children demands a special approach.

-

Children’s organs are at different stages of development — and so are their minds.

-

Clinics take steps to build a comfortable, kid-friendly environment for children participating in clinical trials.

Will the shot hurt? Will it hurt when they take blood? Can I watch TV? And will there be food? (If you’re going to make a mark on history, at least there ought to be snacks.)

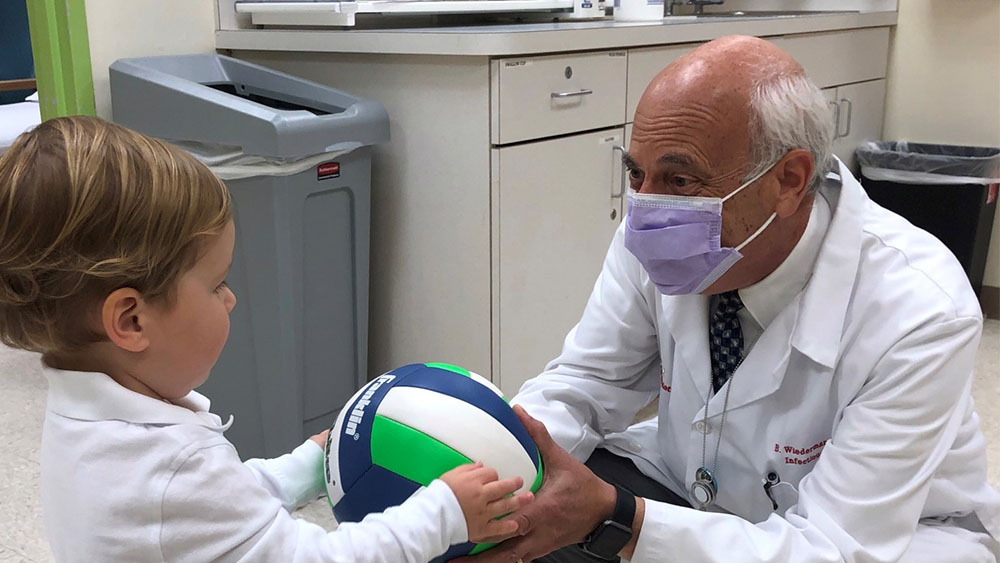

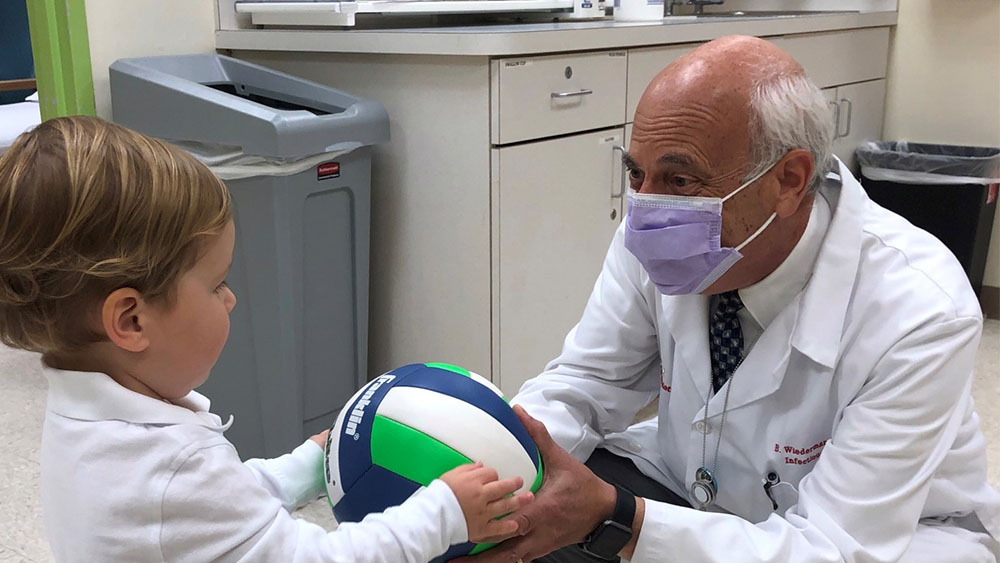

These are some of the most common questions Bernhard Wiedermann, MD, MA, got while registering children for studies of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. Since the summer of 2021, thousands of children across the country between the ages of 6 months and 11 years have received the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna mRNA vaccines to collect data on their safety and effectiveness.

Wiedermann is the lead investigator of the Pfizer-BioNTech trial at Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C. Each time he meets with a parent and child who are considering joining the study, he carefully explains what they can expect. He describes how the child will get shots of either the vaccine or a placebo, have their nose swabbed, and get their blood drawn so scientists can do tests. And yes, Wiedermann says, if a parent or guardian says it’s OK, the child can watch TV and have their choice of something to eat.

The shots, swabs, and blood draws are how pharmaceutical companies are collecting the data to show whether these two mRNA vaccines are safe and effective for children. The vaccines already went through months of testing in adults, leading to emergency use authorization or full approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). But children require a very different approach.

Researcher Bernhard Wiedermann plays with a young participant in the Pfizer-BioNTech trial at Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C. Photo courtesy of Children’s National Hospital.

Researcher Bernhard Wiedermann plays with a young participant in the Pfizer-BioNTech trial at Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C. Photo courtesy of Children’s National Hospital.

What It Takes to Build Clinical Trials for Kids

Clinical trials for kids differ in many ways from those for adults. One crucial difference is the dose.

Children’s organs are at varied stages of development, which affects how quickly they absorb or break down the ingredients of a drug or vaccine. There is no standard formula to calculate the right dose based on what works for adults; the only way to figure it out is by enrolling children in studies.

The vaccine trials for children have three overlapping phases with staggered start dates. Testing starts with children from early elementary age to 11 years old, then from around 2 to 6 years old, and finally from 6 months to 2 years old. For each group, the first step is to run a study to find the best dose.

A study at the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health (CVD) tackled this task for the Moderna vaccine. The research is being supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. “We wanted to see whether or not the children should receive the same dose as an adult or some lower dose than that,” said James Campbell, MD, MS, professor of pediatrics and physician-scientist at the CVD. Campbell leads the UMSOM vaccine trial. “For Moderna, the adult dose is 100 micrograms. We’ve been testing children with 100, with 50, with 25 to see, is there any difference in the safety or any side effect difference? Is there any difference in the immune response?”

Based on their ongoing vaccine trial, the Moderna researchers determined that 6- to 11-year-olds should get half of the adult vaccine dose. With that information, they launched the second portion of the study to determine the vaccine’s safety and efficacy for that age group. In turn, the dose for the older set influences dose testing for the next younger age group, so the start of each stage of the trial is staggered by several weeks. The Pfizer-BioNTech trial was conducted similarly.

COVID-19 Vaccines for Children and Teens

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) shares information on COVID-19 vaccines for children, including where to get them, safety information, and dosage guidance.

Pfizer provides a coloring book to pediatric participants in COVID-19 vaccine trials. Copyright: Pfizer Inc.

Pfizer provides a coloring book to pediatric participants in COVID-19 vaccine trials. Copyright: Pfizer Inc.

Smaller Study, Larger Demand

The children’s vaccine trials are much smaller than the original trials in adults. “Instead of having 30,000 to 45,000 people — half who get the vaccine and half the placebo — we’re enrolling more like a few thousand in each of these age groups,” Campbell said. The total enrollment numbers for the two children’s vaccine trials are expected to range from 8,000 to 13,000 participants.

The children’s trials have fewer participants because they have different goals. Researchers check the children’s immune response and see how it compares with antibody levels and immune activity that protect adults or teens. The researchers also track side effects to make sure they are no worse than what adolescent or adult participants have reported.

Adult trials need more participants to be able to directly measure the effectiveness of the vaccine. That measurement includes comparing the percentage of people who go on to develop COVID-19 in the placebo and vaccinated groups. In children, researchers measure the immune response to the vaccine instead.

Because the trials are smaller, these studies will also deliver results sooner than the adult trials. Although it took nine months from enrolling the first adult to obtaining emergency use authorization for the first COVID-19 vaccine, Pfizer-BioNTech announced initial results from its studies for 5- to 11-year-olds in September 2021, only six months after launching the trials. The FDA will review that data before deciding whether to authorize the vaccine for that age group.

There has been no shortage of volunteers for the trials. At UMSOM, which has also conducted vaccine trials for adults and teenagers, thousands of families recorded their names on a general interest contact list — even before the university announced it would be a site for the pediatric trial.

At Children’s National Hospital, “We’ve had far more parents who have registered their children as being interested than we have slots,” Wiedermann said. More than 30 children were on the waiting list for every participant in the trial. As the highly transmissible Delta variant has become more prominent and cases rise, parents are increasingly flooding the telephone lines, he said. There simply aren’t enough staff to answer all the calls. “I feel sometimes like the bad guy because so many parents are anxious to have their children enrolled, but there aren’t near enough slots,” Wiedermann said.

“There is a lot of emphasis placed on transparency and in the way that the investigator approaches the different age groups that are attended to. Just because they’re 7 doesn’t mean they’re like every other 7-year-old.” —Vanessa Madrigal, MD

Protecting Participants’ Rights — at Any Age

Before a study starts, a special panel reviews the language that study investigators will use to explain the study to participants — what the investigators hope to learn, what they are asking participants to do, and the options open to participants throughout the study. To reinforce the idea that participants agree to join a research study freely, investigators are also careful to explain that participants can ask questions, change their minds, or even leave the study at any time.

That is part of every clinical trial, no matter how old the participants are. However, researchers can get consent from adults directly. With kids, the process has more layers.

One principle that guides researchers in explaining studies to kids is the rule of sevens. It presumes that children younger than 7 do not have the capacity to understand research or to decide about their own participation. By age 14, most children can do both. In between, some children may understand some aspects of the research.

Technically, children — typically, individuals below age 18 — cannot give consent, said Vanessa Madrigal, MD, a critical care specialist and director of the ethics program at Children’s National Hospital. In their place, parents grant permission for their child to participate, and children who can give assent are asked to do so. In practice, investigators take great care in explaining the steps of a trial to children and parents alike.

The expectations for researchers are high: “There is a lot of emphasis placed on transparency and in the way that the investigator approaches the different age groups that are attended to,” Madrigal said. Researchers also make sure to allow for children’s individual needs. “Just because they’re 7 doesn’t mean they’re like every other 7-year-old,” Madrigal said.

“For any child who’s verbal and understanding, I always ask what questions they have,” Wiedermann noted. While their parents sign the paperwork, the kids are asked to give their verbal assent. Some studies include a line to confirm a child’s assent on the consent form itself.

In addition, to ensure that participants in trials are protected, Children’s National Hospital assigns an independent advocate for each trial, part of a program the hospital has had in place for decades. Madrigal fills this role for all trials conducted at the hospital, which means she is available to answer questions about a study and respond to any concerns.

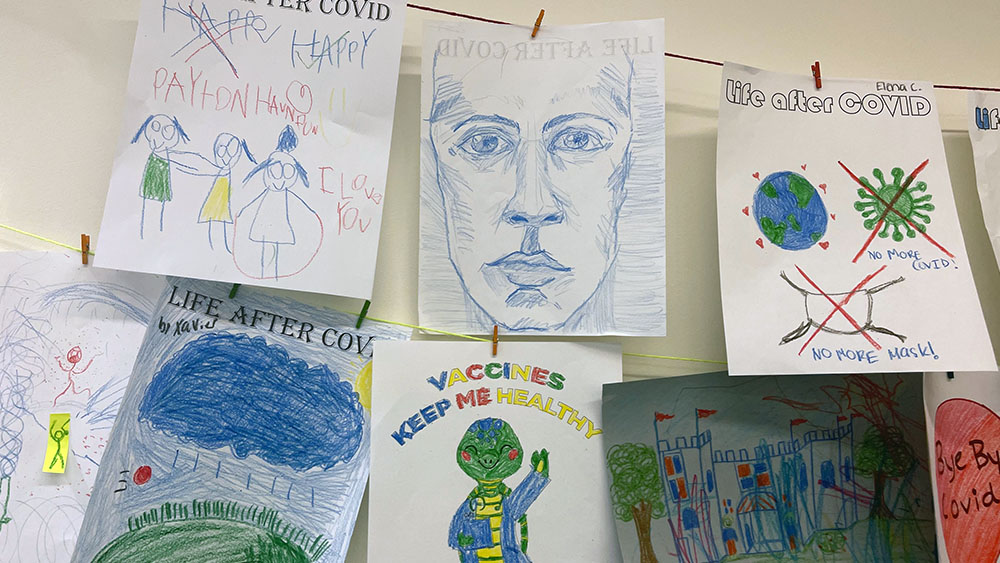

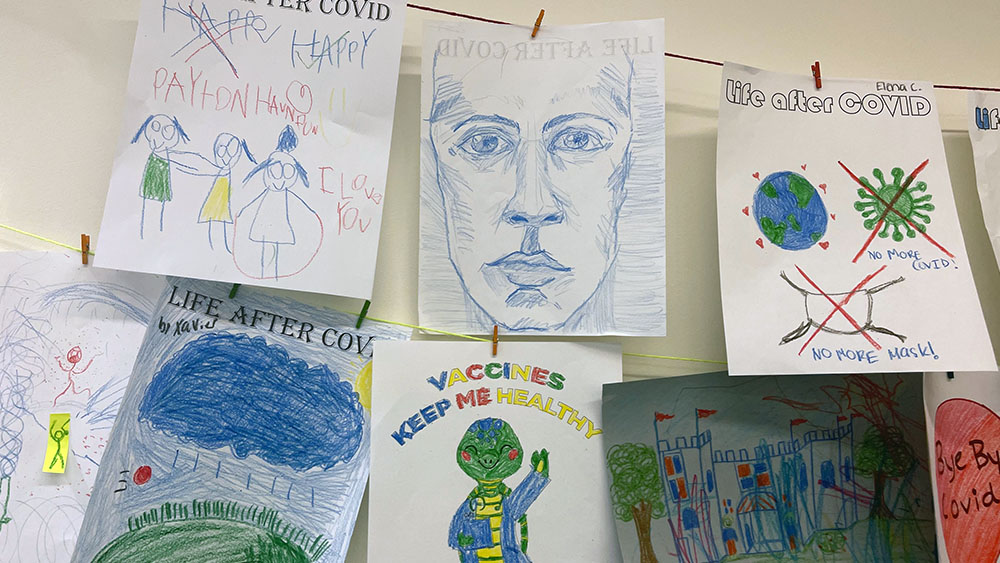

The walls at the University of Maryland School of Medicine’s Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health are decorated with artwork by young participants, imagining life after the COVID-19 pandemic. Photo courtesy of January Payne.

The walls at the University of Maryland School of Medicine’s Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health are decorated with artwork by young participants, imagining life after the COVID-19 pandemic. Photo courtesy of January Payne.

A Historic Moment for Children

The COVID-19 vaccine study consists of a series of screening questions and basic measurements, like height, weight, and vital signs. The children get vaccine shots at two visits a few weeks apart — the same as for adult vaccinations — and have their blood drawn for testing before and after the shots. After each shot, the child or an adult sends daily updates, recording any reactions such as redness, irritation, swelling, or fever. Families are asked to report any COVID-19 symptoms that might develop. Follow-up visits are scheduled to check for any long-term changes in health. The study team may stay in touch with the family for up to two years after the child initially gets the vaccine.

Needles are apt to make a kid anxious. But the truth is, Wiedermann explains, that every child’s perception will be different. “Even nasal swabs can be more uncomfortable or scary for children,” he said. Staff also stock clinic rooms with anesthetic spray or numbing cream to alleviate the pain of an injection or blood draw.

In some cases, it helps to have extra moral support. If a child in the study is concerned about what will happen during the visit, investigators may call on specialists whose job it is to explain unfamiliar or scary procedures, like shots, to a child. They may talk through the process, listen to the child’s concerns, play-act an appointment, or even accompany the child during the procedure.

Parents and staff also do their best to make the environment a comfortable one for participants, with TV, games, art supplies, and the occasional visit from a support dog.

The CVD’s walls at UMSOM are decorated with artwork done by young participants in the vaccine trials. The children are asked to draw what life will look like when COVID-19 is over, and their visions depict everything from cross-country visits to family to getting on the school bus again.

“Sometimes kids aren’t able to express in words, but you really can understand how they feel from what they draw,” said Campbell.

“Some of the older kids have an idea that they are participating in a historic event,” Wiedermann said. “I’m just hoping I’m around another 20 years and may have a chance to talk to some of the kids when they are grown.”

An official website of the United States government

An official website of the United States government