Article Highlights

-

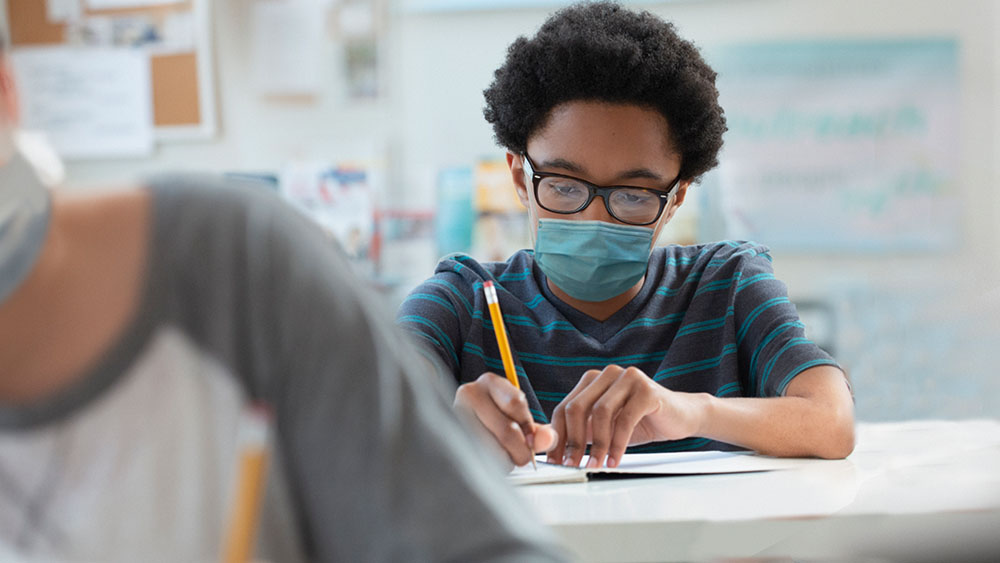

Not all students have equal access to remote schooling, and school closures may have a larger impact on underserved populations.

-

NIH’s RADxSM initiative funds research on how to use COVID-19 testing to help control the pandemic.

-

Researchers in North Carolina, Missouri, California, and other states are studying how testing can keep students and staff safe.

Many children went through the entire 2020-21 school year without attending class in person. When children do not go to school in person, they miss out on not only face-to-face instruction but also meals, speech therapy, after-school programs, and more. In addition, not all students have adequate electronics, internet access, or adult supervision at home. The transition to virtual learning was difficult for almost all students and parents, but it may have had particularly large impacts for minorities, socially and economically disadvantaged children, and children with developmental disabilities or health problems.

In many school districts, parents of Black and Latino children were less likely to send their children back to school even when they had the option. Black and Latino communities were particularly affected by the pandemic, and parents may not have felt safe sending children into schools. In addition, access to vaccines was a problem for many in the spring of 2021.

Offering safe in-person school in the 2021-22 school year will help ensure that children in underserved groups do not fall farther behind. NIH’s RADx℠ Underserved Populations (RADx-UP) program aims to increase COVID-19 testing for vulnerable and underresourced populations. Now RADx-UP is funding projects across the country to learn what role COVID-19 testing can play in safely returning students, teachers, and other staff to schools. For example, testing could identify asymptomatic infections or shorten quarantine times for people who have been exposed to COVID-19.

The new projects are part of the Safe Return to School Diagnostic Testing Initiative, which includes studies in a variety of schools and communities, with a variety of testing approaches. These projects will build evidence that school administrators can use to make sure all children are able to return to school safely and stay there. The initiative is managed by NIH’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

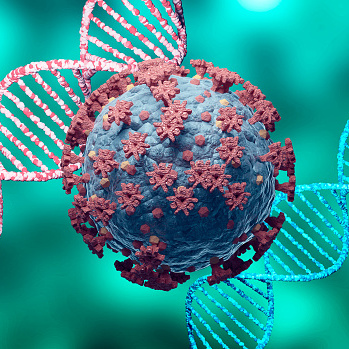

Masks are very effective at slowing the spread of the virus that causes COVID-19.

Masks are very effective at slowing the spread of the virus that causes COVID-19.

Collaborating in North Carolina

In July of 2020, administrators in North Carolina wanted to open schools but didn’t know how to do it safely. So they asked for help from researchers like Kanecia Zimmerman, M.D., M.P.H., a pediatric intensive care doctor at Duke University with a long history of studying the needs of children. She leads the NICHD-funded Pediatric Trials Network (PTN), which includes more than 100 pediatric hospitals, academic institutions, and other clinical sites.

In response, Zimmerman joined with school administrators and other scientists to start the ABC Science Collaborative and think through how to return students to school safely.

Some North Carolina schools opened as early as August 2020, while others stayed closed. As schools reopened, scientists in the collaborative collected data and monitored outcomes. “The data supports that masking or vaccination are the most effective ways to prevent transmission,” Zimmerman said. “If you want to be safe and prevent transmission, the best thing is to have a masking mandate.”

Based on the data, which Zimmerman and her colleagues published in the journal Pediatrics in January 2021, North Carolina schools were required to offer in-person education across the state starting in March of 2021 and have been sharing their data with the collaborative’s scientists ever since. The data also helped inform federal guidelines on returning to school.

The RADx-UP project now helps Zimmerman and her colleagues understand what role COVID-19 testing can play. They are offering testing at several schools with large numbers of Black and Latino students. People with symptoms or who have been exposed to the virus can be tested. Also, students, teachers, and staff can sign up for screening — that is, periodic testing without the presence of symptoms. A subset of these people are tested weekly at each participating school.

Masks are so effective that Zimmerman suspects the data will show that screening is not needed to control transmission within schools if everyone wears masks. But in schools where students and staff do not wear masks, testing could help keep track of outbreaks and allow people who are infected or exposed to quarantine quickly. And one important benefit of testing could be to help reassure parents that school is safe. The researchers are also interviewing parents of Black and Latino children to understand how they feel about sending children back to school and whether testing makes a difference.

Zimmerman hopes her research helps schools prepare for the future. “This is the ultimate goal of all of these return-to-school projects: How can we use the lessons that we’ve learned, so we’re not scrambling for the next pandemic?”

The ABC Science Collaborative

This collaborative began as an effort to help North Carolina schools and expanded to include scientists across the country who are helping their local schools.

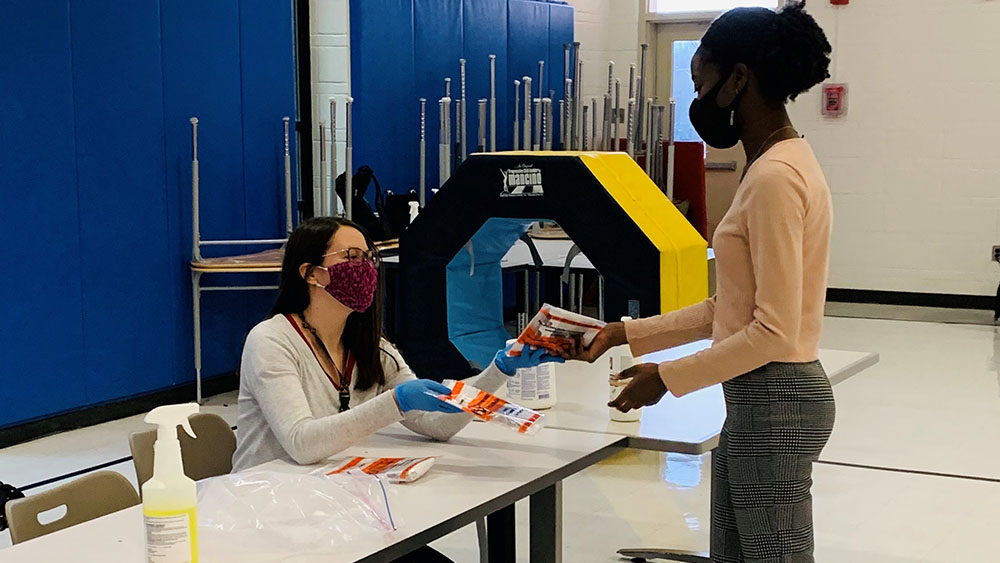

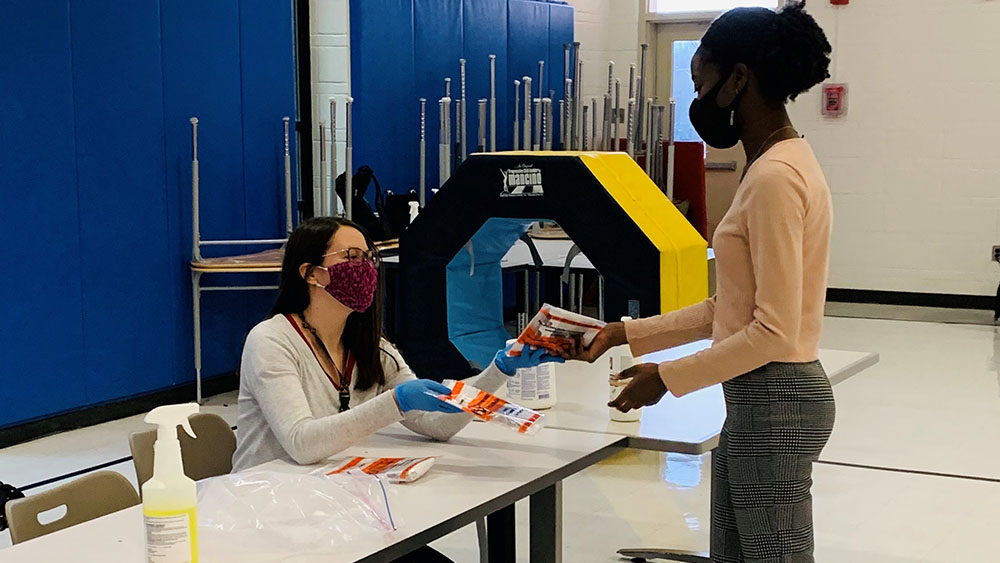

Researchers at Washington University in St. Louis have brought COVID-19 testing to six schools for children who cannot be in mainstream classrooms. Photo courtesy of Christina Gurnett, M.D., Ph.D.

Researchers at Washington University in St. Louis have brought COVID-19 testing to six schools for children who cannot be in mainstream classrooms. Photo courtesy of Christina Gurnett, M.D., Ph.D.

A Special School District in Missouri

Being out of school was particularly hard on children with intellectual or developmental disabilities. Many rely on school services such as social workers, aides, and therapists. “Then, suddenly, the child’s at home, and the parents have to serve all those roles,” said Christina Gurnett, M.D., Ph.D., a pediatric neurologist at Washington University in St. Louis and co-leader of a RADx-UP study on COVID-19 testing for children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Taking on all of those roles was even harder for parents who could not work from home.

Gurnett’s project brings testing to six schools for children who cannot be in mainstream classrooms. The schools are part of the St. Louis Special School District, which serves children with a wide range of disabilities and emotional problems in communities around St. Louis.

Children with intellectual or developmental disabilities may be particularly vulnerable to COVID-19. Some developmental disorders cause problems with the immune system or lungs that make those children more susceptible to respiratory viruses. Some children could have trouble complying with rules about masks and other measures to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. And many children in these six schools have a personal health aide to help them with daily activities — so they can’t stay physically distanced.

Gurnett and her colleagues received funding from RADx in the summer of 2020 and started adding study participants that fall, as staff began to return to school buildings. Students, teachers, and staff can sign up for weekly testing through the study.

The new RADx-UP funding awarded in the spring of 2021 enabled Gurnett and her colleagues to expand the study to the Kennedy Krieger Schools, four schools in Maryland that serve populations similar to those the St. Louis area schools serve. In both Maryland and Missouri, the researchers will be studying how best to communicate with parents that they can sign their kids up for weekly surveillance testing, as well as how best to persuade teachers and staff to participate. The funding also makes it possible to offer testing during the summer session and when school reopens in the fall.

To understand more about families’ opinions and concerns about sending kids to school in person, the researchers are also working with advocacy groups to interview parents of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities across the country.

The weekly testing helped allay the fears of St. Louis Special School District teacher Meg Tegerdine, who works with fifth and sixth graders who struggle with social and emotional interactions. When she went back to school in person, she said, “I was very scared that I was going to possibly transmit something to a family member or to one of my students.” The weekly test helped reassure her; not only could she be sure that she did not have COVID-19 herself, but she also knew that it wasn’t spreading in her school.

“If you want to be safe and prevent transmission, the best thing is to have a masking mandate.” —Kanecia Zimmerman, M.D., M.P.H.

Testing Los Angeles

Los Angeles Unified School District is the second largest school district in the country, with more than 600,000 students at more than 1,000 schools. In July of 2020, L.A. Unified officials approached the University of California, Los Angeles, for help. The school district, which planned to use COVID-19 testing to help bring children back to school safely, wanted scientific advice.

Moira Inkelas, Ph.D., M.P.H., a public health researcher at UCLA, got involved to help the district understand parents’ attitudes about testing and return to school. In the summer of 2020, the district surveyed parents to find out what might make them feel safer. Many parents said that testing would help. Schools welcomed students back starting in April of 2021 while continuing to offer online schooling.

Making the return to school equitable is a major concern for L.A. United officials. School district data in 2020 showed that Black and Latino children were having more trouble accessing online education. When children were given the option to return to school in the spring, there were huge disparities in who returned, particularly in elementary schools. In some communities, more than two-thirds of elementary school students returned to school in person; in others, it was less than one-fifth. Officials could see that more children were coming back to elementary schools in whiter, more affluent areas.

Inkelas and her colleagues confirmed that finding by combining the school district’s data with data about how the pandemic affected each school’s neighborhood. They found that elementary school students were less likely to go back to school in neighborhoods that were more affected by COVID-19 and had fewer people vaccinated. Those neighborhoods were more likely to be made up of low-income minority families.

The researchers are also interviewing parents to hear their feelings about returning to school and will continue the interviews over time to see how those feelings change. This may show that testing influences parents’ feelings about safety or maybe that new outbreaks or variants influence their thinking. “We’re all going through this together, and it’s hard to predict how we might feel a couple of months from now,” Inkelas said.

In the 2021-22 school year, with the new RADx-UP funding, the researchers will analyze weekly testing data that identifies cases of COVID-19 as well as any transmission that happens within the school.

All of these studies will help move schools closer to their goal: to provide an education in person while keeping everyone involved safe — and, Inkelas said, getting kids into the classroom and getting them “some normality in their social life.”

Sources

- The ABC Science Collaborative. (2021, June 30). COVID-19 and schools: The year in review and a path forward. Retrieved July 23, 2021, from https://abcsciencecollaborative.org/year-in-review-path-forward/

- Zimmerman, K. O., Akinboyo, I. C., Brookhart, M. A., Boutzoukas, A. E., McGann, K. A., Smith, M. J., Maradiaga Panayotti, G., Armstrong, S. C., Bristow, H., Parker, D., Zadrozny, S., Weber, D. J., Benjamin, D. K., Jr, & ABC Science Collaborative. (2021). Incidence and secondary transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infections in schools. Pediatrics, 147(4), e2020048090. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-048090

An official website of the United States government

An official website of the United States government