Article Highlights

-

Many people recover quickly from COVID-19, but some do not.

-

NIH has launched a new initiative to study long-term symptoms.

-

The goals of the research include finding better treatments for long COVID.

Chimére Smith felt her first symptoms of COVID-19 on a Sunday morning in March 2020. “It almost felt like I could feel the virus entering into my body,” she said. It started with a tickle in her throat. “As the day wore on, I started to feel worse and worse,” she said. The tickle turned into a sore throat. “I did not feel like myself. I haven’t felt like me since March 22, 2020.”

Over the next few days, new symptoms appeared — shortness of breath, spinal pain, dizziness, trouble thinking. By the end of the week, Smith was weighed down with fatigue. And more symptoms kept appearing. In late April, she lost most of the vision in her left eye. By summer, she had to be in a room by herself, in the dark, because she couldn’t stand the light. “I couldn’t even think long enough or concentrate enough to have conversations with people,” she said.

Many people recover quickly from COVID-19. But some, like Smith, do not. For some people, symptoms can continue months after recovery and may involve multiple organs. Together, these long-term effects of COVID-19 are referred to as “Long COVID,” included under the umbrella of Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection, or PASC. Some patients refer to themselves as “long-haulers.”

In February 2021, NIH launched the PASC Initiative to bring together researchers and clinicians to study how to prevent and treat the symptoms and long-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection. The initiative supports research to collect data from people who have had COVID-19, both with and without long-term symptoms, and compare them with people who may never have been infected by SARS-CoV-2. The cohort will include both children and adults and will emphasize diversity to ensure that the findings apply to the communities who have been most affected by COVID-19. The goal is to find ways to prevent and treat these long-term symptoms.

"I did not feel like myself. I haven’t felt like me since March 22, 2020." — Chimére Smith

Chimére Smith celebrating her 37th birthday, a year before she got sick. Photo courtesy of Chimére Smith.

Chimére Smith celebrating her 37th birthday, a year before she got sick. Photo courtesy of Chimére Smith.

Exploring a New Condition

As with any new disease, there are many unanswered questions about Long COVID, said Michael Saag, M.D., an infectious disease doctor and researcher at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “This is a frontier. We have no idea what’s around the corner,” Saag said. “As researchers, our goal is to methodically go about defining it, studying it, understanding it, and then developing treatments that we can test and see if they work.”

One of the questions is how exactly to define PASC.

In December 2020, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases held a virtual Workshop on Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 to summarize what was known about PASC and identify key gaps in knowledge. Saag chaired a session at that workshop, and Smith was part of a panel of people who shared their experiences with Long COVID.

In addition, a group called Patient-Led Research for COVID-19, which conducts research on long-term symptoms of COVID-19, defined Long COVID in a December publication as “a collection of symptoms that develop during or following a confirmed or suspected case of COVID-19, and which continue for more than 28 days.” They found that some of the most common symptoms were fatigue, symptoms that worsened after physical or mental activity, shortness of breath, trouble sleeping, and “brain fog” — trouble thinking clearly.

The biggest question, according to Saag, is what is happening in the body to cause the long-term problems. He suspects that SARS-CoV-2 somehow disturbs the immune system; instead of ramping down as it normally would after it wins the battle with a virus, it keeps on fighting against nothing.

Saag himself came down with COVID-19 in March 2020, just a few days after the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic. He lost his senses of smell and taste and much of his hearing, and he was fatigued for months. Although his senses of smell and taste eventually came back, he still needs hearing aids a year later.

The goal of the NIH-funded research through the PASC Initiative is to find better treatments for PASC. For now, doctors can address the various symptoms — and validate patients’ concerns. “One of the main things we do now that provides a good amount of comfort to people is at least acknowledging that it’s real,” Saag said. “It’s not their imagination.”

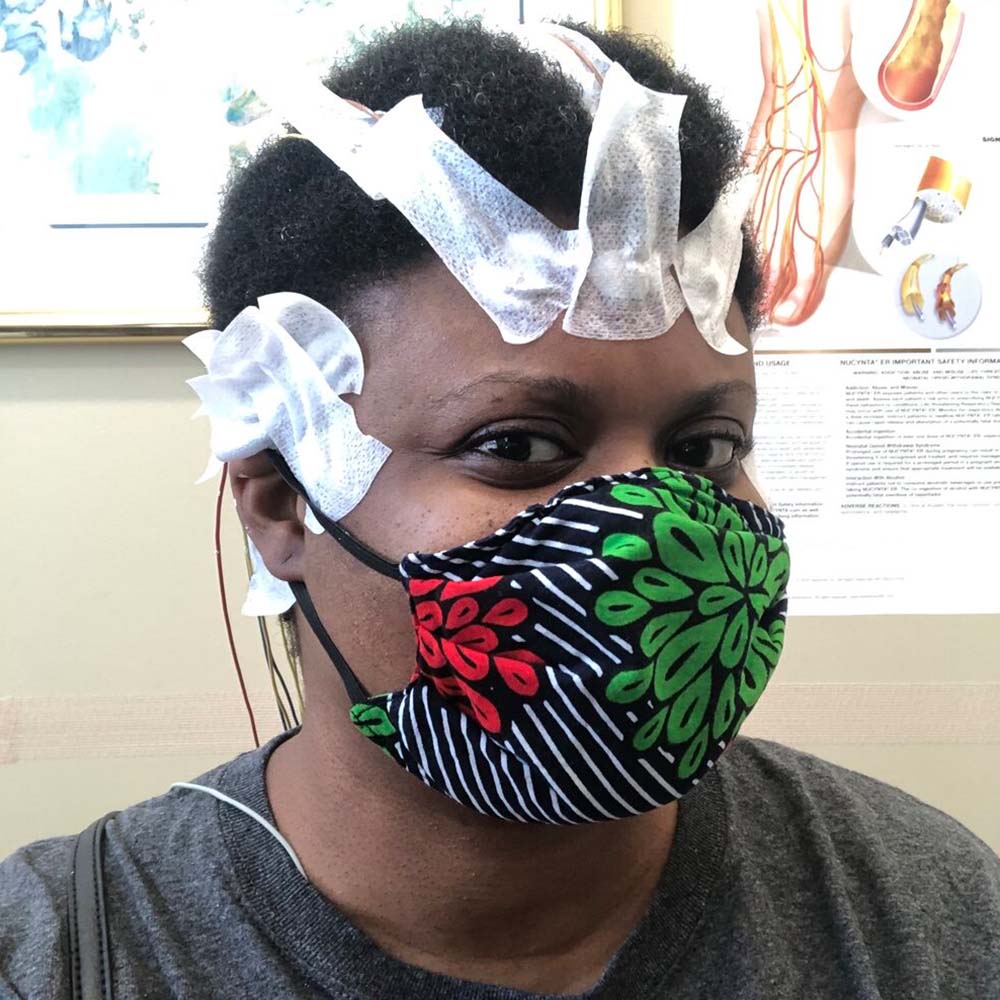

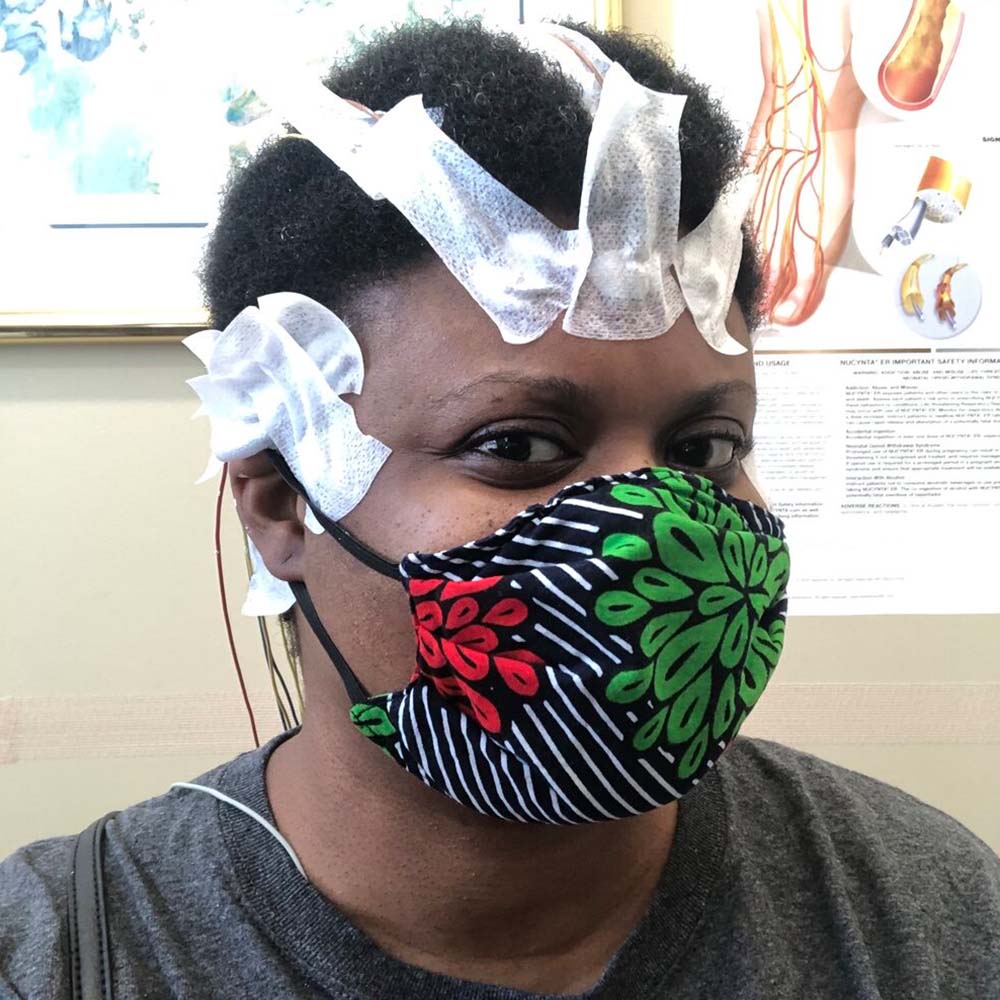

Chimére Smith has had a variety of tests to monitor her Long COVID symptoms, including this electroencephalogram, which measures the electrical activity of the brain. Photo courtesy of Chimére Smith.

Chimére Smith has had a variety of tests to monitor her Long COVID symptoms, including this electroencephalogram, which measures the electrical activity of the brain. Photo courtesy of Chimére Smith.

Road to Improvement

Smith did not get that level of support. For months, she struggled with her symptoms and sought medical help. “I was turned away, I wasn’t listened to, I wasn’t respected, I wasn’t honored, and I wasn’t heard,” she said.

Smith felt that her race was a major factor in her treatment. “I’d been taught to be nice and to respect all people and, as a Black woman, to keep my head down and work really hard. ‘You’ll have a seat at the table because you won’t cause a ruckus,’” she said. “But that wasn’t saving my life.” Eventually, she realized, she had to try a new approach. “I had to become angry; I had to become very relentless about me and my care,” she said. She connected with local politicians, who looked into her case and got doctors to take her seriously. Cataract surgery brought back her vision, and by carefully managing her energy, she has gotten to a point where she can function again.

With a good job and health insurance, Smith felt she was relatively privileged. Now she wants to help people who have even more trouble navigating the health system, such as the parents of the mostly low-income children in her classes at a Baltimore City middle school. She is writing a grant for her church in northwestern Baltimore — she refers to her neighborhood as “the hood” — to become a center for educating people on Long COVID and how they can help themselves.

Before she got sick, Smith was teaching a unit on Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Her last classroom memory is of a heated debate about whether Hermia should go against her father’s will to have a relationship with Lysander. “They wanted her to run away with the person she really wanted to be with,” she said. Observers from the state board of education were in her class that week. “My kids were on fire,” she said.

Now she doesn’t know whether she will ever be healthy enough to go back to work. “I get emotional — that was the last week for me in my career, possibly,” she said. “If it has to end, I’m very happy it ended that way.”

An official website of the United States government

An official website of the United States government