Article Highlights

-

Alcohol consumption increased more during the COVID-19 pandemic than in the last 50 years.

-

Alcohol-related illness and deaths also rose during the pandemic.

-

NIH research has contributed to tools that help people reduce problem drinking and improve their health.

Severe illness, grief, isolation, disrupted schooling, job loss, economic hardship, shortages of food and supplies, mental health problems, and limited access to health care — these are just some of the sources of stress people faced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

To cope, many people turned to alcohol despite the risk of developing alcohol-related problems, including problem drinking and alcohol use disorder (AUD).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines excessive alcohol use as binge drinking, heavy drinking, alcohol use by people under the minimum legal drinking age, and alcohol use by pregnant women. AUD is a clinical diagnosis that indicates someone’s drinking is causing distress and harm. AUD can range from mild to severe, depending on the severity of the symptoms. Severe AUD is sometimes called alcohol addiction.

We spoke with George F. Koob, Ph.D., director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), to learn about the pandemic’s effects on alcohol use and related harms. Koob is an expert on the biology of alcohol and drug addiction and has been studying the impact of alcohol on the brain for more than 50 years. He is a national leader in efforts to prevent and treat AUD and to educate people about risky alcohol use.

George F. Koob, Ph.D., director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Photo courtesy of NIAAA.

George F. Koob, Ph.D., director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Photo courtesy of NIAAA.

How concerned should we be about people drinking to deal with the stress of the COVID-19 pandemic?

GEORGE F. KOOB, PH.D.: Drinking because of a big crisis is not unusual. For example, we saw spikes in alcohol use in response to the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center. Alcohol consumption by Black and African Americans in New Orleans almost tripled when their communities were devastated by Hurricane Katrina in August 2005. Many people drank more after the 9/11 attacks.

The COVID-19 pandemic was similar to other major catastrophes as it caused widespread illness and loss of life. But there was another factor that really affected people: isolation from their fellow human beings. People had to maintain social distancing to slow the spread of COVID-19. For many, stress from the pandemic, including from social isolation, resulted in an increase in drinking.

It was really no surprise that during the first year of the pandemic, alcohol sales jumped by nearly 3%, the largest increase in more than 50 years. Multiple small studies suggest that during the pandemic, about 25% of people drank more than usual, often to cope with stress. Sales of hard liquor, or spirits, accounted for most of the increase.

With other disasters, we’ve seen that these spikes in drinking last 5 or 6 years and then alcohol consumption slowly returns to usual levels. We hope that the high rates of alcohol use and negative health effects will decline over time as we return to more typical interactions with each other.

Resources to Help People Evaluate Their Relationship With Alcohol

NIAAA’s free, research-based resources can help cut through the clutter and confusion about how alcohol affects people’s lives. These resources are available in multiple languages.

Have researchers found any trends in alcohol-related deaths and health problems during the pandemic?

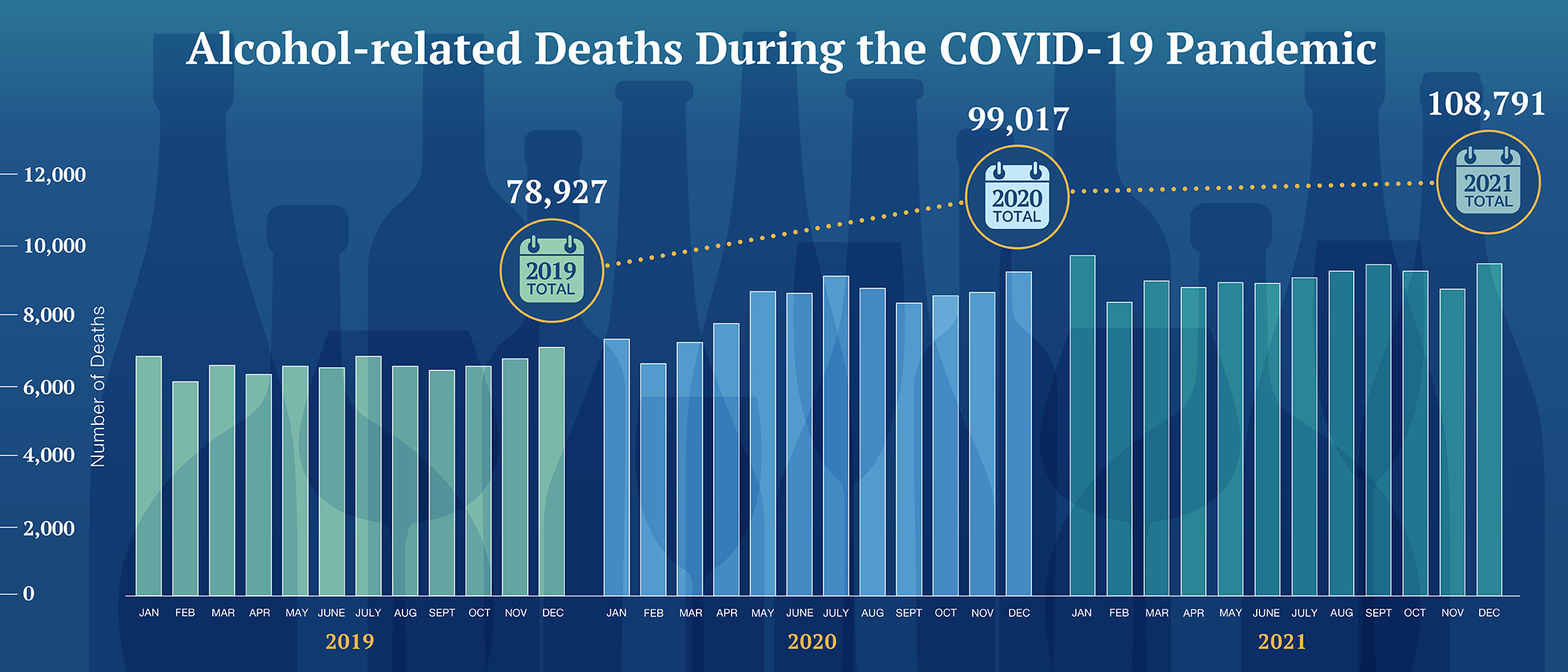

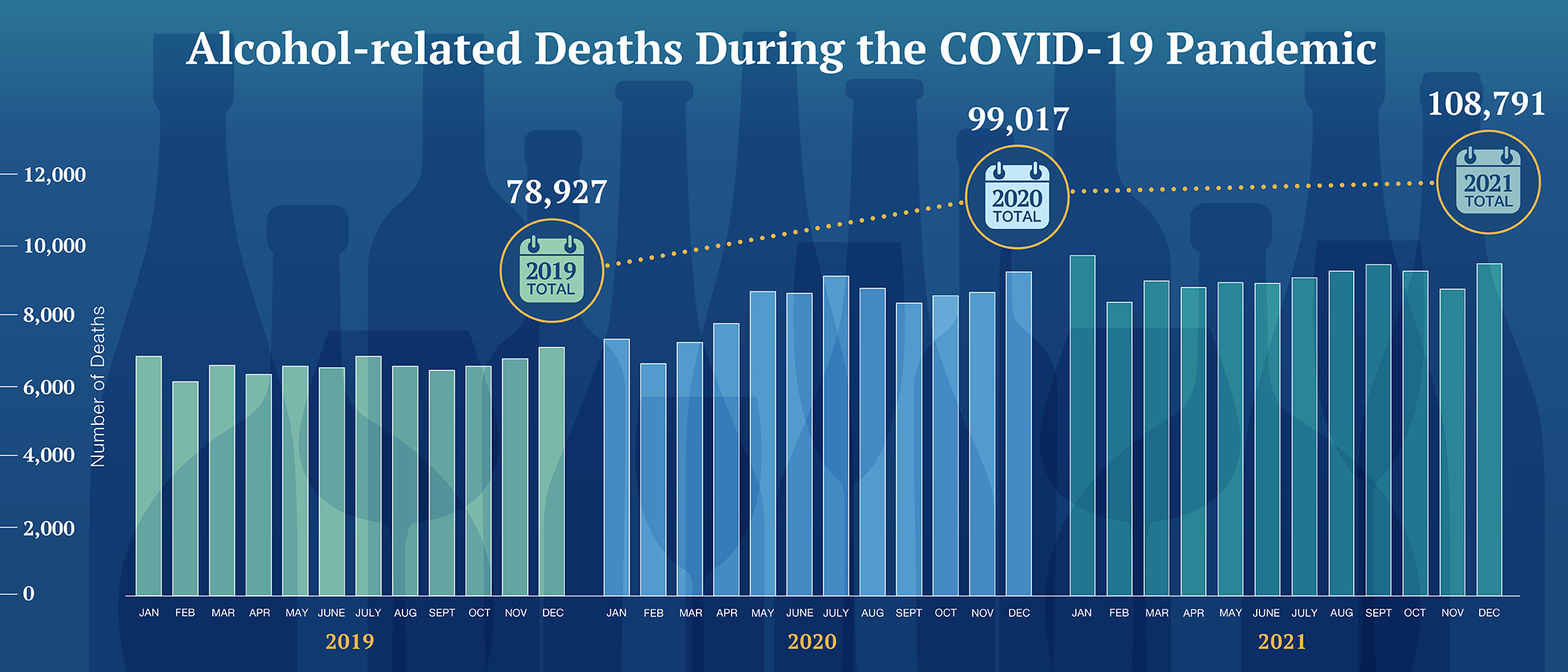

KOOB: Yes, we’ve certainly been seeing higher levels of disease and death linked with alcohol use, and it’s pretty dramatic. During the first 2 years of the pandemic, the number of death certificates listing alcohol as a factor soared from 78,927 to 108,791 — an increase of nearly 38%. We saw the largest increases in deaths related to drinking among people between the ages of 25 and 44.

We’ve also seen more people end up in hospitals due to alcohol misuse and its consequences, including withdrawal symptoms and liver disease. People seeking liver transplants because of alcohol misuse are younger than ever, with many transplant centers reporting that some of their patients haven’t even reached the age of 30. Unfortunately, deaths due to alcohol-linked liver disease increased by more than 22% during the pandemic.

The figure above shows the number of alcohol-related deaths each month in 2019 (before the pandemic) and in 2020 and 2021 (during the pandemic). Source: NIAAA.

The figure above shows the number of alcohol-related deaths each month in 2019 (before the pandemic) and in 2020 and 2021 (during the pandemic). Source: NIAAA.

Do some people have a higher risk for AUD triggered by events like the pandemic?

KOOB: The pandemic has shone a light on how stress and negative emotions drive a good bit of alcohol misuse. In general, people who already drank in risky ways before the pandemic were more likely to increase their use during the pandemic. Also, caregiving responsibilities, stress, depression, and anxiety were linked with increased drinking during the pandemic.

The effects of the pandemic on alcohol-related problems have not been the same for everyone, though. One example is an NIAAA-supported study showing that fewer college students had AUD symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The pandemic has shone a light on how stress and negative emotions drive a good bit of alcohol misuse. —George F. Koob, Ph.D.

Will there be long-term consequences of pandemic-related alcohol misuse?

KOOB: Some people will have trouble cutting back on their drinking and will have a higher risk of AUD. As the pandemic wanes, people are gathering socially again. We’re seeing some “rebound” risky drinking behaviors; that does sometimes happen after a period of alcohol deprivation.

Also, during the period of shelter-in-place orders, children may have been exposed to unhealthy behaviors related to alcohol use. This could influence their future risk for problem drinking, AUD, and health problems related to alcohol use.

Finally, some jurisdictions loosened alcohol restrictions during the pandemic. More restaurants and bars started selling alcohol for off-site consumption. Online sales of alcohol more than tripled in April 2020. Many policy changes and trends are likely to continue long after the pandemic ends, increasing the risk of alcohol-related problems. NIAAA conducts and funds research into the effects of these factors.

What are some healthier options for coping with stressful events and avoiding risky drinking behaviors?

KOOB: The good news is, there’s been a big change in our conversation about alcohol, especially for young people: Dry January, “sober curious,” Sober October, mocktails, zero-proof wine and beer, and dry bars are spreading across the United States. These trends reflect a greater awareness of alcohol’s harmful effects and can inspire behavior change. Here are some other ways to cope:

-

First, interact with your fellow human beings. Be like a bumblebee going from flower to flower. Reach out to your friends and family, one person after another.

-

Second, exercise! Exercise helps with nearly every ailment, be it heart disease, lung disease, or depression.

-

Third, know the facts: NIAAA offers all sorts of resources to help people learn about alcohol and its effects, assess their relationship with alcohol, and find treatment providers.

Sources

- Ballard, J. (2016). What is Dry January? British Journal of General Practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 66(642), 32. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp16X683173

- Beaudoin, C. E. (2011). Hurricane Katrina: Addictive behavior trends and predictors. Public Health Reports, 126(3), 400-409. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335491112600314

- Cerda, M., Vlahov, D., Tracy, M., & Galea, S. (2008). Alcohol use trajectories among adults in an urban area after a disaster: Evidence from a population-based cohort study. Addiction, 103(8), 1296-1307. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02247.x

- McPhee, M. D., Keough, M. T., Rundle, S., Heath, L. M., Wardell, J. D., & Hendershot, C. S. (2020). Depression, environmental reward, coping motives and alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 574676. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.574676

- National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors. (December 2020). Policy brief: Disasters and substance use: Implications for the response to COVID-19. https://nasadad.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Policy-brief_-Disasters-and-Substance-Use.pdf

- NIAAA. (2023). Alcohol-related deaths, which increased during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, continued to rise in 2021. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/news-events/research-update/alcohol-related-deaths-which-increased-during-first-year-covid-19-pandemic-continued-rise-2021

- NIAAA. (2022). Surveillance report COVID-19: Alcohol sales during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/surveillance-covid-19/COVSALES.htm

- Rodriguez, L. M., Litt, D. M., & Stewart, S. H. (2020). Drinking to cope with the pandemic: The unique associations of COVID-19-related perceived threat and psychological distress to drinking behaviors in American men and women. Addictive Behaviors, 110, 106532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106532

- Schmidt, R. A., Genois, R., Jin, J., Vigo, D., Rehm, J., & Rush, B. (2021). The early impact of COVID-19 on the incidence, prevalence, and severity of alcohol use and other drugs: a systematic review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 228, 109065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109065

- White, A. M., Castle, I. P., Powell, P. A., Hingson, R. W., & Koob, G. F. (2022). Alcohol-related deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA, 327(17), 1704-1706. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.4308

An official website of the United States government

An official website of the United States government