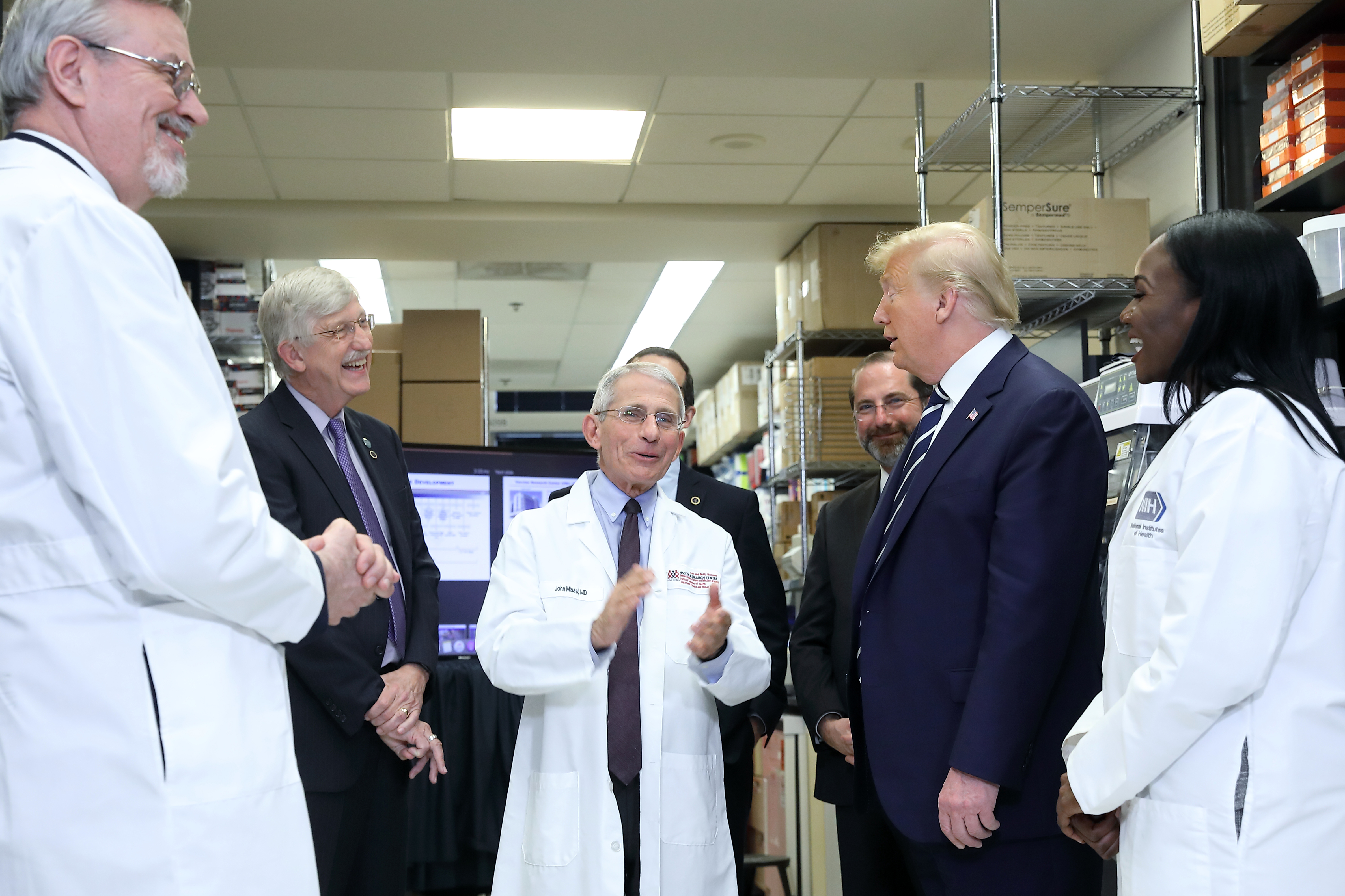

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

What you need to know

Developing a vaccine and bringing it to market often takes many years. But because of work that NIH was already doing when the COVID-19 pandemic began, researchers were able to come up with vaccines for this new virus much faster.

What did this research do?

There are many different coronaviruses. SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is just one; others can cause illnesses like the common cold.

Years before the COVID-19 pandemic began, experts at the NIH Vaccine Research Center (VRC) were studying coronaviruses to find out how to protect against them. The scientists chose to focus on one “prototype” coronavirus and create a vaccine for it. That vaccine could then be customized to fight different coronaviruses. It was important that this vaccine be three things:

- Fast. If a pandemic began — like the COVID-19 pandemic did in late 2019 — researchers would need to be able to adapt the vaccine and produce a lot of doses very quickly.

- Reliable. The vaccine had to be extremely effective in humans.

- Universal. The vaccine would have to work for many different coronaviruses, since it is not always possible to predict which viruses will spread quickly or become dangerous.

How did the research help?

Using their prototype coronavirus, the researchers studied the spike protein, which appears on the surface of coronaviruses. These spikes let the coronavirus latch onto cells in our body. When the body’s immune system sees the spike protein, it makes antibodies to try to protect the body from infection. This makes it a good vaccine target.

Traditionally, researchers would try putting the spike protein in the vaccine. When injected, the vaccine would stimulate a person’s immune system to protect them from a particular coronavirus. But the team knew that during a pandemic, it would take too long to make large amounts of a specific spike protein.

So, they studied a faster way to get a spike protein into the body. This new approach is to inject mRNA instructions for the spike protein into a person’s muscle. The muscle cells then make the spike protein. And then the body’s immune system makes the needed antibodies to protect itself.

Did it work?

Yes. Having this prototype approach, along with coronavirus research from labs around the world, made it possible for scientists to spring into action when the pandemic hit. Many vaccines take 10 to 15 years to reach the public. But the timeline for the COVID-19 vaccine was very different.

The COVID-19 outbreak in China was first reported publicly on December 31, 2019. By the second week of January 2020, researchers in China published the DNA sequence of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

The VRC worked with a company called Moderna to use this information to quickly customize their prototype approach to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. By early February, a COVID-19 vaccine candidate had been designed and manufactured. This vaccine is called mRNA-1273. By March 16, 2020, this vaccine had entered the first phase of clinical trials. Other vaccines, including a similar one from Pfizer and BioNTech SE, entered clinical trials not long after.

On December 18, 2020, after demonstrating 94 percent efficacy, the NIH-Moderna vaccine was authorized by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for emergency use. Just days earlier, the similar Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine had become the first COVID-19 vaccine to be authorized for use in the United States.

Why is this research important?

With the development of safe, effective vaccines, we can protect ourselves, our loved ones, and our neighbors against the virus — and end the pandemic.

Where can I go to learn more?

- Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases explains how she worked with the VRC to develop the vaccine prototype.

NIAID’s Prototype Pathogen Preparedness Plan

- Read more about how NIAID had prepared for years to be able to shorten the time it takes to develop a vaccine.

Coronaviruses | NIH: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)

- Learn about NIAID’s extensive and ongoing coronavirus research.

Sources

Garnett, C. (2020, December 11). Fast, Reliable, Universal: Corbett Recounts Quest for Covid Vaccine. NIH Record. https://nihrecord.nih.gov/2020/12/11/corbett-recounts-quest-covid-vaccine

Moderna, Inc. (n.d.). Moderna’s Work on a COVID-19 Vaccine Candidate. Retrieved December 10, 2020, from https://www.modernatx.com/modernas-work-potential-vaccine-against-covid-19

News and Stories

Read stories about the efforts underway to prevent, detect, and treat COVID-19 and its effects on our health.

An official website of the United States government

An official website of the United States government