Article Highlights

-

As researchers create and test vaccines, safety is top of mind at each step of the process.

-

Experts review the study plan before it even starts and monitor safety throughout.

-

Tracking reactions to the vaccine is key.

-

As important for saying it’s safe: Who’s taking part?

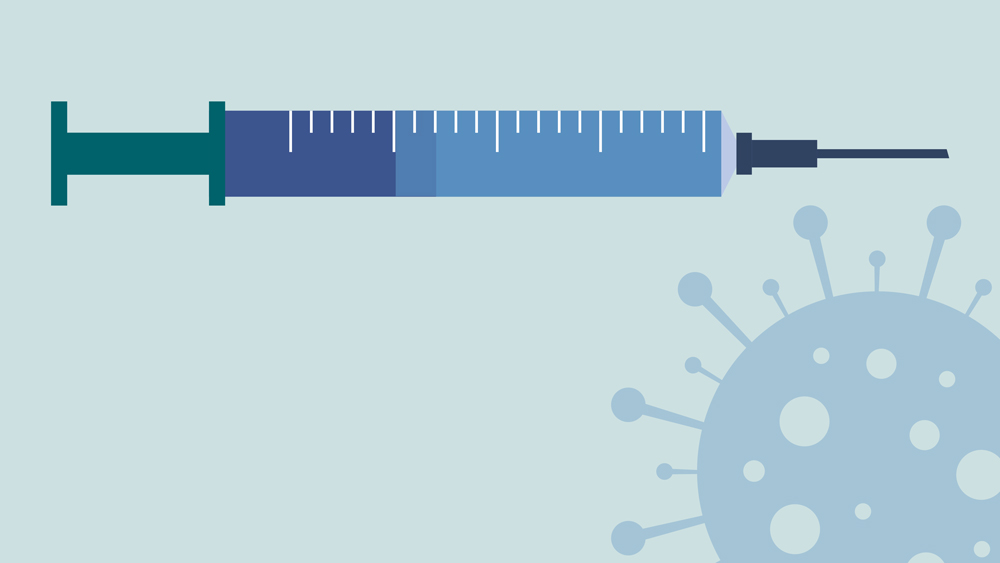

As a member of a data safety and monitoring board (DSMB), Lisa A. Cooper, M.D., M.P.H., an internal medicine physician, epidemiologist, and health equity researcher at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and Bloomberg School of Public Health, has a unique perspective on research.

A DSMB is a group of experts who review data from studies in real time. The groups are independent, with no ties to either the researchers or the funders of the study. They can decide for themselves how often they meet and how to conduct their meetings.

Having seen the process up close, Dr. Cooper said, she is confident in the safety of vaccines — and can share that confidence with others. “It’s one thing to try to encourage people to try to participate in research, to tell them about the research procedures that are in place to protect them and how well trained the scientists and staff are,” she said. “It’s a whole other thing to say, ‘You know what, I’ve sat on the other side of this, where I’ve been able to look at the data that’s being collected.’”

Dr. Cooper is one of countless individuals across the country who lend their expertise to monitor the safety of participants in clinical trials. From the early days of vaccine development to the later studies that enroll thousands of people, safety monitors like Dr. Cooper make suggestions to ensure that study participants — and ultimately vaccine recipients — are protected. Safety monitors constantly weigh the benefits of a vaccine against the risks of harm.

NIH’s Community Engagement Alliance (CEAL) Against COVID-19 Disparities works closely with communities hardest hit by COVID-19. As part of that effort, CEAL is highlighting the efforts of these safety monitors through the CEAL Scientific Pathway.

Doctors like Lisa A. Cooper (left) and Jaime G. Deville (right) volunteer their expertise to ensure the safety of clinical trial participants, including in trials of COVID-19 vaccines.

Doctors like Lisa A. Cooper (left) and Jaime G. Deville (right) volunteer their expertise to ensure the safety of clinical trial participants, including in trials of COVID-19 vaccines.

Before the Trial Begins

Before anyone joins a clinical trial for a vaccine, outside experts and community members review the researchers’ plan for testing the new vaccine. This plan, known as the study protocol, details how the study will run: How many people will be in the study? Who can join? What data will the researchers collect? How often will they check on participants, and for how long? How will they know whether the vaccine is a success?

Jaime G. Deville, M.D., a pediatrician at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, was one of the reviewers who approved the protocol for the Phase 3 Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccine clinical trials for COVID-19. More than 100 institutions including UCLA participated in the studies, each enrolling a few hundred people. Together, these local groups made up the 30,000 to 40,000 people nationwide needed to test each vaccine.

Dr. Deville’s approval of UCLA’s protocol was part of his work on a group of experts and community members that is known as an institutional review board (IRB). The IRB’s role included reviewing the study’s safety measures and making sure they adequately protected the people who joined. IRB approval is required before any research study can begin enrolling participants.

IRB members pay close attention to how the researchers plan to decide whether the vaccine being tested is safe. “Each study team’s protocol has rules,” Dr. Deville said.

Once the IRB gives the study team the green light, researchers can start enrolling participants, giving them the vaccine, and collecting the data that will show how safe and effective it is. Experts at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration do their own review of the data and authorize the use of a vaccine only if the data collected show that it is safe and effective.

“As the only people that are unblinded as to who is getting what treatment, we have to preserve the integrity of the study.” —Lisa A. Cooper, M.D., M.P.H.

Keeping an Eye on a Trial in Progress

Dr. Cooper is an expert in health equity who has conducted extensive research on how to build trust between the medical community and patients, especially patients from communities of color. These concerns are proving to be important to acceptance of the vaccine, alongside the data on its safety and how well it works.

Between 2015 and 2020, Dr. Cooper chaired the DSMB that monitored a series of NIH-sponsored Ebola vaccine trials in West Africa. Only weeks after that effort ended, she was asked to join the board overseeing several COVID-19 vaccine trials at NIH.

Vaccine studies, like many medical studies, are double-blinded. That means no one knows who is getting a placebo and who is getting the “real” vaccine — not the person receiving the shot, not the person giving it, and not the scientists or the organizations funding the research. This ensures that no one can give away any clues that might influence the results, even inadvertently. For example, a researcher who knew who got the vaccine and who didn’t might treat those two kinds of participants differently.

While the study is going on, DSMB members are unblinded, meaning they are among the only ones who can see data showing which participants received the vaccine. Researchers rely on the DSMB to look behind the curtain and recommend any changes to the study that might be needed. For example, if an experimental vaccine were causing severe reactions (which was not the case with any of the COVID-19 vaccines that have been authorized for use in the United States), only the experts on the DSMB would be able to discover that.

“As the only people that are unblinded as to who is getting what treatment, we have to preserve the integrity of the study,” Dr. Cooper said. That means the DSMB members can’t tell researchers what they’re seeing unless and until the DSMB members recommend that the study be stopped.

The Journey of a Vaccine

Learn about the four phases of clinical research, what questions researchers try to answer in each, and how a vaccine is developed, approved, and manufactured.

Safety in Diversity

For this DSMB, it turned out, the issue of who hadn’t enrolled was just as important. Early in testing for the COVID-19 vaccines, it became clear that most participants joining the trial were not from the communities being hit hardest by the disease.

“Some of the earlier trials were more focused on enrolling people in different age groups more quickly and on balancing the participants by gender,” Dr. Cooper recalled. A racially and ethnically diverse group of participants had not been a top priority, so the DSMB weighed in. Based in part on her research on health care experiences for people in a variety of communities, Dr. Cooper knew that some people would not be persuaded of a vaccine’s safety if people like them were not represented among the study participants.

The point was to get people with diverse circumstances and beliefs to participate, she said. “If we do find out that it’s effective, other people who are like that will also say, ‘You know, I saw somebody that looked like my uncle. So, if they could get the vaccine, I might be willing to try it.’”

DSMB members wanted to know: “Who are you reaching out to? Who are you partnering with? Where are you doing recruitment? Who is on your staff that’s doing the recruitment? We gave a lot of input into that,” Dr. Cooper said, “because we felt that if there wasn’t diversity in the trials, [then] the public might not perceive that the vaccine therapies would be relevant to them.”

It worked. The DSMB’s recommendations helped shift the recruitment focus. In the end, the percentage of Hispanic participants exceeded Hispanic communities as a share of the U.S. population. Although final percentages for African American, Asian, American Indian and Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander communities were lower than in the general population, the studies addressed initial imbalances and ultimately achieved greater racial diversity than many previous studies.

Video: Dr. Lisa A. Cooper, Safety Monitor

Learn more about Dr. Cooper and others on the scientific pathway from discovery to treatment.

DSMBs are independent from researchers and study sponsors, ensuring the safety of participants and recommending ways to improve trials before they start and while they are in progress.

DSMBs are independent from researchers and study sponsors, ensuring the safety of participants and recommending ways to improve trials before they start and while they are in progress.

Adding to a Legacy of Safety

Of course, vaccines are intended to keep us safe by protecting us and our loved ones from disease. They do this so well that many people take it for granted how safe we are thanks to vaccines.

“People don’t realize that we had millions of cases of measles. Every year we had tens of thousands of cases of paralytic polio; everybody knew someone who had it,” Dr. Deville said. “That was a fact of life, [but] these diseases are eradicated now.”

A pediatric infectious disease specialist, Dr. Deville has done decades of research on whooping cough (pertussis), a very contagious disease that is particularly dangerous to children; HIV; respiratory syncytial virus (RSV); and pneumococcus. Recently, his research has included investigations of vaccine safety in pregnant women, people with weak immune systems from HIV or other causes, and children, including infants.

As a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, routine vaccination programs have been disrupted in many countries, sometimes causing diseases that had been under control to re-emerge. “I have seen firsthand the loss and devastation of this pandemic,” Dr. Deville said. In his role as safety monitor — and soon as an investigator in a COVID-19 vaccine trial for children — he has also played a part in helping curb its spread.

Some 17 months after the COVID-19 pandemic started gaining momentum in the United States, deaths and hospitalizations fell to their lowest levels since March 2020, thanks to the 150 million people who were vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2. However, in the summer of 2021, the number of cases began to rise again, with hospitalizations increasing among the unvaccinated. Two vaccines — the Moderna mRNA vaccine and the Johnson & Johnson viral vector shot — have been authorized for adults, and the Pfizer mRNA vaccine has been authorized for children 12 and older. The Pfizer vaccine has also received full FDA approval for people over the age of 16. The clinical trials showed that the vaccines were extremely effective and safe. They continue to be found effective as new and more contagious strains of the virus have spread.

Many people do still have doubts, and those perspectives must be heard and respected, Dr. Cooper said. When she speaks with these people, she reassures them that she and others were thinking of everyone’s safety while monitoring the trials. She uses her front-row seat in the vaccine testing process to answer questions, erase misconceptions, and give patients information they can use to make decisions about the vaccine.

“I think it brings a lot of credibility to my voice,” said Dr. Cooper.

An official website of the United States government

An official website of the United States government