Article Highlights

-

MIS-C is a rare complication from COVID-19 that affects children.

-

NIH is funding the MUSIC Study, part of the CARING for Children with COVID program, to understand MIS-C in children.

- The study will also look for genetic predispositions to MIS-C.

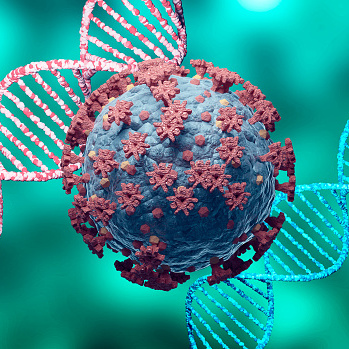

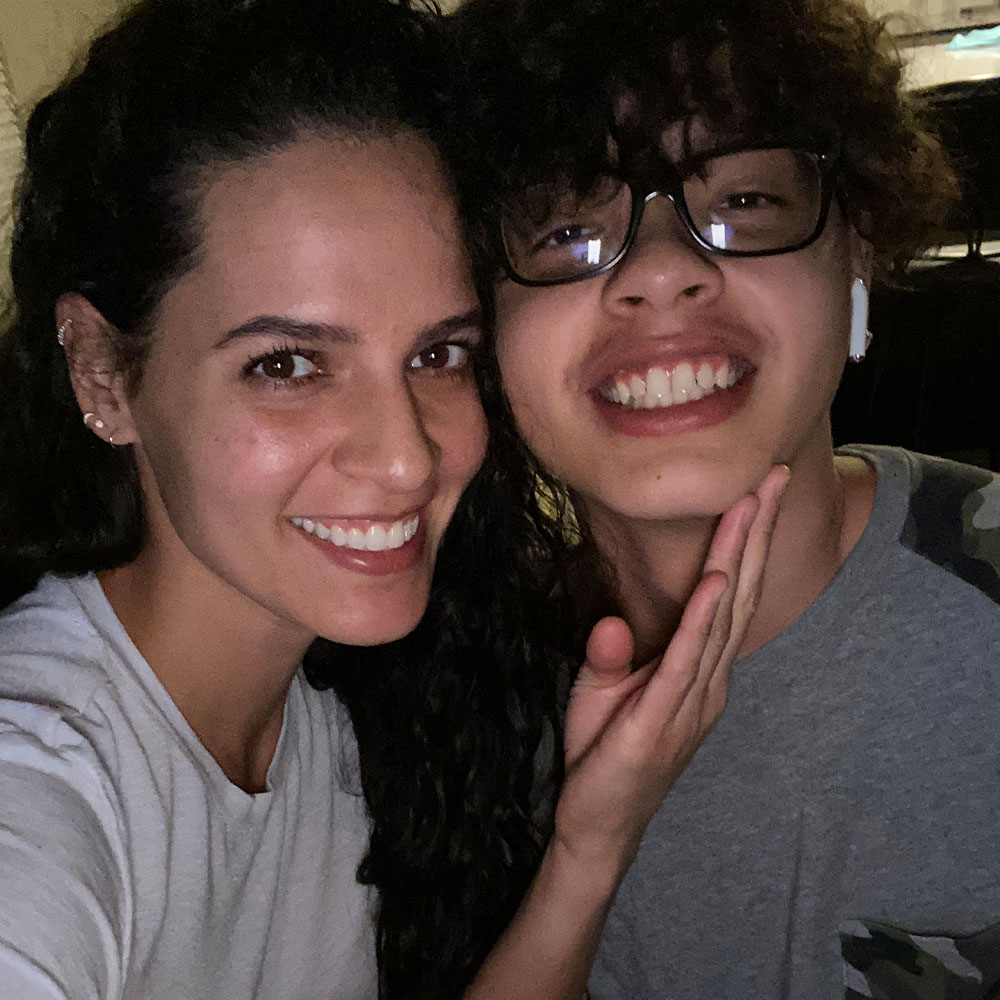

In December 2020, 14-year-old Abie Martinez and his mom, Cendy Marquez, came down with headaches and body aches. With their mild symptoms, Cendy, a home care nurse in West Haven, Utah, guessed that they had COVID-19, but she didn’t get the two of them officially tested. Their symptoms cleared up, and they went back to their daily lives.

Six weeks later, Abie’s left leg didn’t feel right, and his neck hurt a little. “I was thinking we were probably overdoing it at the gym,” Cendy said. They go a few times a week.

But Abie’s symptoms got worse. Throughout the week, he felt tired and had developed a headache, fever, a weird rash on his arm, and diarrhea.

“My body was just shutting down on me. I didn’t have enough energy,” said Abie.

By Friday morning, Cendy suspected Abie had meningitis and took him to his pediatrician, who immediately sent him to the local emergency room. “They tested him for meningitis and come to find out, it was not meningitis,” Cendy said. “It was COVID.”

The condition Abie had is a rare complication that children and teens can develop two to six weeks after having COVID-19, even if they don’t have symptoms. Called multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C, pronounced by reading the individual letters), the illness can affect the heart and other organs. Researchers with the Long-Term Outcomes after the Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome In Children (MUSIC) Study are seeking explanations for this mysterious illness and long-term outcomes for children infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

Abie Martinez, right, seen here with his mom Cendy Marquez, is helping researchers understand a rare but serious complication of COVID-19. Courtesy of Cendy Marquez.

Abie Martinez, right, seen here with his mom Cendy Marquez, is helping researchers understand a rare but serious complication of COVID-19. Courtesy of Cendy Marquez.

Emergency flight

At their local emergency room, Abie was extremely dehydrated and his kidneys were shutting down, so he was flown to Intermountain Primary Children’s Hospital in Salt Lake City, Utah.

“Life Flight just rushed in, and they took him away. Neither I nor his dad could go in the plane with him. He was all by himself,” said Cendy. “And I mean, that hit me as a health care worker. For me not to know what was going on with my son, that was really hard.”

At Primary Children’s Hospital, Abie and his parents met pediatric cardiologist Ngan Truong, M.D., the co-leader of the MUSIC Study. The study is part of NIH’s CARING for Children with COVID program, which brings together researchers from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development to focus on illnesses related to COVID-19.

By joining the MUSIC Study, Abie is helping researchers understand why some children and adolescents develop MIS-C after having COVID-19 and how MIS-C affects them in the long term.

“I tell people with children who’ve had COVID to look out for these symptoms. This happened to my son.” —Cendy Marquez

Caption: Rashes (like the one here on Abie’s arm) can signal MIS-C, if they occur with heart issues, fever, or other symptoms. Courtesy of Cendy Marquez.

Caption: Rashes (like the one here on Abie’s arm) can signal MIS-C, if they occur with heart issues, fever, or other symptoms. Courtesy of Cendy Marquez.

Overdrive

The virus that causes COVID-19 can infect many different systems throughout a person’s body — nose, lungs, gut, kidneys, skin, almost every organ. To fight off the virus, the immune system kicks into gear and attacks the virus. In most cases, the virus stops reproducing. Then the immune system goes back to lying in wait for the next germ.

Researchers have found that in children with MIS-C, the immune system goes into overdrive, continuing to fight after getting rid of the virus. Inflammation, such as redness and swelling around a cut, is part of the immune system’s defensive response, but in children with MIS-C, the immune system’s overreaction causes organs to become inflamed — the same organs that COVID-19 affects.

But researchers aren’t sure why this happens to some children but not others or why the immune system goes into overdrive in the first place. They also do not know whether children will recover completely, whether there will be long-lasting damage, or whether there are underlying genetic or environmental aspects to consider. The MUSIC Study is designed to help answer these questions.

MUSIC Study

The MUSIC Study will contribute to a better understanding of the best way to treat children with MIS-C.

The heart of MIS-C

To answer these questions, Dr. Truong and her colleague Jane Newburger, M.D., M.P.H., at Boston Children’s Hospital in Massachusetts are working with a network of researchers at another 31 hospitals across the country and in Canada. The study is being conducted with the help of the NHLBI-funded Pediatric Heart Network.

One of the more concerning symptoms of MIS-C is what happens to the heart. The heart of someone affected by MIS-C can become inflamed and have a hard time pumping blood to the body. Also, the blood vessels can become too relaxed and widen. Both of these events cause low blood flow and can lead to dangerously low blood pressure, a condition called shock. Patients experiencing shock can require intensive care and blood pressure medicines.

To be diagnosed with MIS-C, children and adolescents have to be sick enough to be hospitalized. Their stays average about a week. Dr. Truong said that the hearts of most patients get back to full strength before they leave the hospital. How long the kids take to fully recover is one of the questions the study seeks to answer.

“Given the newness of the illness, parents have been very happy to be involved to help us learn more about the disease. And I have to say, we are so thankful for that.” —Ngan Truong, M.D.

From left, sisters Abrie and Allessia join their older brother Abie at a fall outing to a pumpkin patch and corn maze. Courtesy of Cendy Marquez.

From left, sisters Abrie and Allessia join their older brother Abie at a fall outing to a pumpkin patch and corn maze. Courtesy of Cendy Marquez.

The study is easy to participate in, said Dr. Truong. Most of the information the study will gather will be from care the child is receiving anyway. This includes electrocardiograms and heart ultrasounds, MRIs, and CT scans. The one test that is not part of standard care — and is optional for study participants — is genetic testing. Looking at a child’s genetic profile might reveal a predisposition for this type of illness.

Researchers will also explore the connection of MIS-C to different racial or ethnic groups, said Dr. Truong. In a study at Boston Children’s Hospital, Dr. Newburger and her colleagues found that African American or Hispanic children were more likely to develop the condition. Lower socioeconomic status was also associated with higher likelihood of MIS-C. The MUSIC Study will help to further explore these risk factors.

Spreading the word

Initially, the plan for the MUSIC Study was to enroll 600 patients and follow them for five years. But Dr. Truong said that seven months in, the study was able to enroll 600 participants, about 20% of the 3,100 MIS-C patients in the United States at the time.

As of July 2021, there are more than 4,000 children who had or have MIS-C in the United States, and the study has received permission to recruit more participants. There are now more than 765 children and adolescents from across the United States and Canada participating. “Given the newness of the illness, parents have been very happy to be involved to help us learn more about the disease. And I have to say, we are so thankful for that,” said Dr. Truong.

Back in West Haven, Abie has mostly recuperated since his five-day stay at Primary Children’s Hospital. “I am doing a lot better. I don’t know about 100%,” said Abie. “I was pretty active. But now I have to keep it slow. I have to work myself up to where I used to be.”

Cendy is sounding the alarm with the people she works with in home health care. “I tell people with children who’ve had COVID to look out for these symptoms. This happened to my son.”

Sources

- Javalkar, K., Robson, V., Gaffney, L., Bohling, A., Arya, P., Servattalab, S., Roberts, J., Campbell, J., Sekhavat, S., Newburger, J., de Ferranti, S., Baker, A., Lee, P., Day-Lewis, M., Bucholz, E., Kobayashi, R., Son, M., Henderson, L., Kheir, J., Friedman, K., & Dionne, A. (2021). Socioeconomic and racial and/or ethnic disparities in multisystem inflammatory syndrome. Pediatrics, 147(5), e2020039933. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-039933

- COVID Music Study (2020). MUSIC Study | Understanding Long Term Outcomes of MIS-C. Retrieved July 11, 2021, from https://covidmusicstudy.com.

An official website of the United States government

An official website of the United States government